Critical Reflection

In Unit 2, my work unfolded as a continual search for home through five overlapping strands: capturing time into matter through repeated, ritualistic gestures; contemplating the body as home; home in the remembered space activated through familial rituals and the domestic; home in the invisible space explored through perception of memory as operative element; and home in the interstitial space, where memory is threaded into matter. While I feel I deepened and intensified my practice through works developed in this period, I also recognise it is still in formation.

I. Capturing Time into Matter through the Language of Repeated, Ritualistic Gestures

In The Phenomenology of Roundness, Bachelard (2014) lingers with the sensation of being is round, through the intersections of elementary phenomenology , metaphysics and poetics. This kind of roundness escapes the surface logic of form, but emerges as a as cosmic unity, a fullness as experienced intimately from within. Bachelard (2014), suggests that even the spoken word round draws the mouth, lips and breath into the shape it names, momentarily embodying its calm and propagating its roundness from within.

In ciliary (2010), Hamilton draws from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s notion of circles, a fundamental, ever-returning form in nature, as the first eye.

..................................................‘The eye is the first circle, the horizon which it forms is the second’ (Emerson quoted in Hamilton, 2025).

For Hamilton (2025), acts of hand making such as, sewing or drawing becomes the first eye, a way of seeing through doing. In ciliary (2010), the thread pulled through cloth becomes a linear gesture that embodies breath, rhythm of the body, and the orbit of the hand, all folding into a circular return – a repetition that is at once temporal and spatial, intimate and expansive.

..................................................‘The eye is the first circle, the horizon which it forms is the second’ (Emerson quoted in Hamilton, 2025).

For Hamilton (2025), acts of hand making such as, sewing or drawing becomes the first eye, a way of seeing through doing. In ciliary (2010), the thread pulled through cloth becomes a linear gesture that embodies breath, rhythm of the body, and the orbit of the hand, all folding into a circular return – a repetition that is at once temporal and spatial, intimate and expansive.

For me, just as Bachelard’s roundness arises through an elementary phenomenology as fullness experienced intimately from within, Hamilton’s circles of the hand as a means of seeing through doing, reads as enfolded roundness experienced through the act of repetitive making. This continuous search for an interior feeling of roundness, I have come to recognise, is the generative force underpinning my practice, as a recurring impulse that surfaces through ritualistic, repetitive making. I associate this feeling of roundness with my feeling at home. In my work, this roundness is experienced through rhythmic acts of repeated gestures like weaving, braiding, emplacing and tracing. These bodily lines that curve and return, circular inscriptions and small orbiting movements, not only activate emotionally charged materials like human and horsehair, satin ribbons and caraway seeds but re-weave relationships between self-material-space, tracing home, not as a geographic location, but as accessed through time, and the language of ritualised, repeated gestures.

II. Contemplating the Body as Home

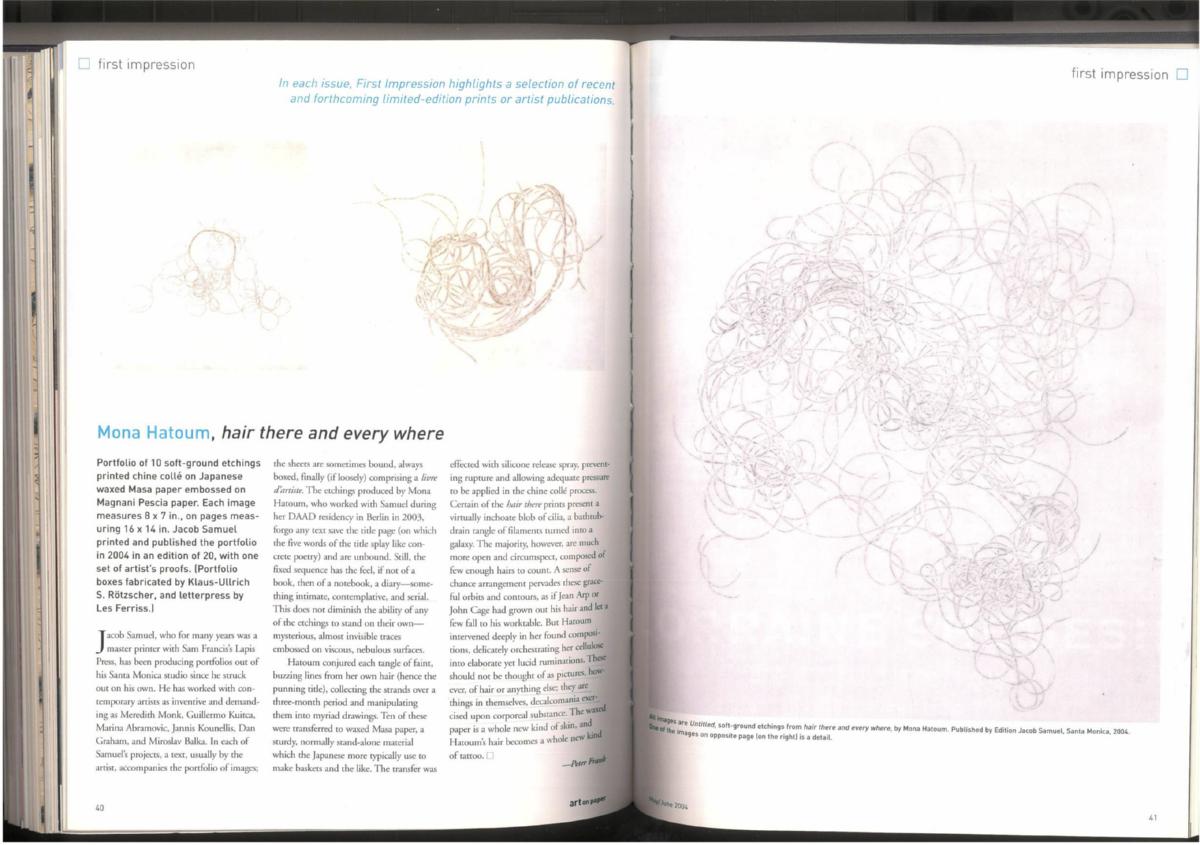

In Hatoum's Untitled (2003), tangled networks of hair are suspended upon white paper surface, loose yet deliberate. As Frank (2004) writes:

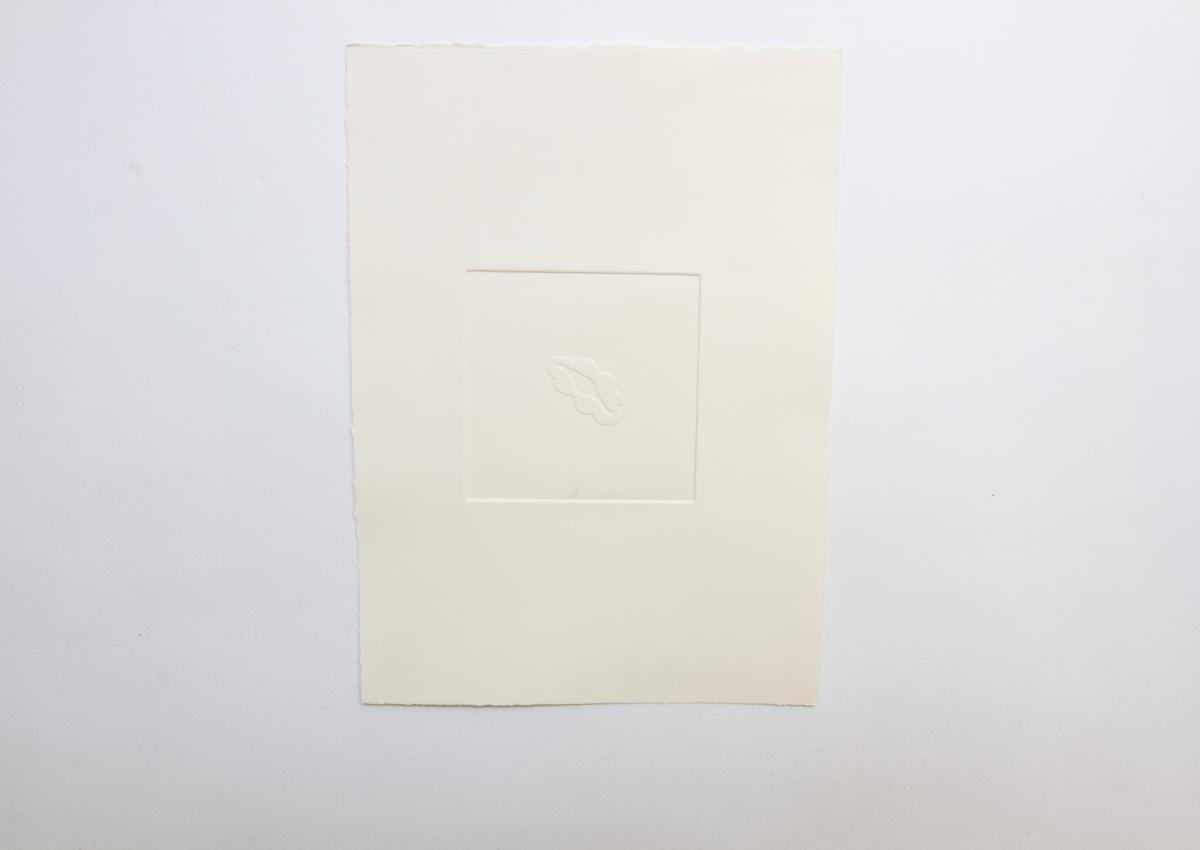

This articulation resonates with how I understand my materials: a residue, imprint and index of bodily presence. Like Hatoum, I consider paper as a kind of skin: absorbent, porous and responsive. My series Transferences (2025) – inspired by Hatoum’s tactile material poetics – a series of hard-ground etching embossments, explore memory as embodied patterns: repeated, elusive and felt. Drawing on misremembered Kalocsa motifs, printed without ink, these etchings allow absence to leave tactile imprint of itself. The paper, like a membrane, an interstitial layer between the self and the collective, capable of recording both physical gestures and emotional residues, becomes the skin of my body, bearing quite inscriptions of lived experiences.

These should not be thought of as pictures, however, of hair or anything else; they are things in themselves, decalcomania exercised upon corporeal substance. The waxed paper is a whole new kind of skin, and Hatoums’ hair becomes a whole new kind of tattoo’ (Frank, 2004).

This articulation resonates with how I understand my materials: a residue, imprint and index of bodily presence. Like Hatoum, I consider paper as a kind of skin: absorbent, porous and responsive. My series Transferences (2025) – inspired by Hatoum’s tactile material poetics – a series of hard-ground etching embossments, explore memory as embodied patterns: repeated, elusive and felt. Drawing on misremembered Kalocsa motifs, printed without ink, these etchings allow absence to leave tactile imprint of itself. The paper, like a membrane, an interstitial layer between the self and the collective, capable of recording both physical gestures and emotional residues, becomes the skin of my body, bearing quite inscriptions of lived experiences.

Rodney’s In The House of My Father (1996-7), a miniature sculpture of a house built from his own skin, destabilises the permanence we typically associate with architecture. Proposing instead a home that is vulnerable, ephemeral, and inseparable from the body’s biography. The skin here functions both as surface and archive, marked by folds, scars, and tonalities like a visceral site of habitation. In Weave of me (2025), I explore similar emotional geographies through the weave of my own collected hair into silk-paj. In this sense, my own hair becomes a thread, a residue, a tactile site of embodied memory, exploring how memory resides in repeated gestures, materials and surfaces.

In Cellscape (2018), Light explores how understanding of our physical being may influence our day-to-day sense of embodiment and identity. The glass becomes a lens, a stand-in for both the body’s fragility and vulnerability, allowing a view to the interior of the body. In Images of Home (2025), glass becomes a window, a surface that let memory breath. Like the window of my Mother’s kitchen or the translucent lens of the eye, it mediates what is seen and what is felt. It is a threshold: not fixed, but flickering – porous, emotional and alive. The house is the body, the body is my home, and glass, like the eye, traces its roundness as a gesture of return to proximity through perception. Ultimately, I think of the body as mutable, absorbent, porous architecture of intimacy, a site: interstitial, vulnerable, mediating surface.

III. Home in the Remembered Space. Familial rituals and the domestic

Mother-Goddess (2025), inspired by a small clay figurine Baldock once gifted his mother, recalls details of the family life of the artist as Kentish hop gatherers to explore how domestic practices shape lived experiences. The hybrid body of the sculpture – half-jacket, half-dress – stitched from hessian wool, a fabric traditionally used for hop sacks, and heavily embroidered with applique, reads as a weaving of memory into matter, where domestic rituals passed through generations are reactivated in the present. Like Baldock (2025), I too, draw from intimate, familial rituals, reactivating memories of interactions with my Mother as a generative force in my making. For instance: my Mother braiding my hair with satin ribbons, embroidering my clothes with Kalocsa motifs, or weaving protective horsehair bracelets. These emotionally charged acts of care, even when fragmented or misremembered, leak into and form the emotional and material grammar of my making.

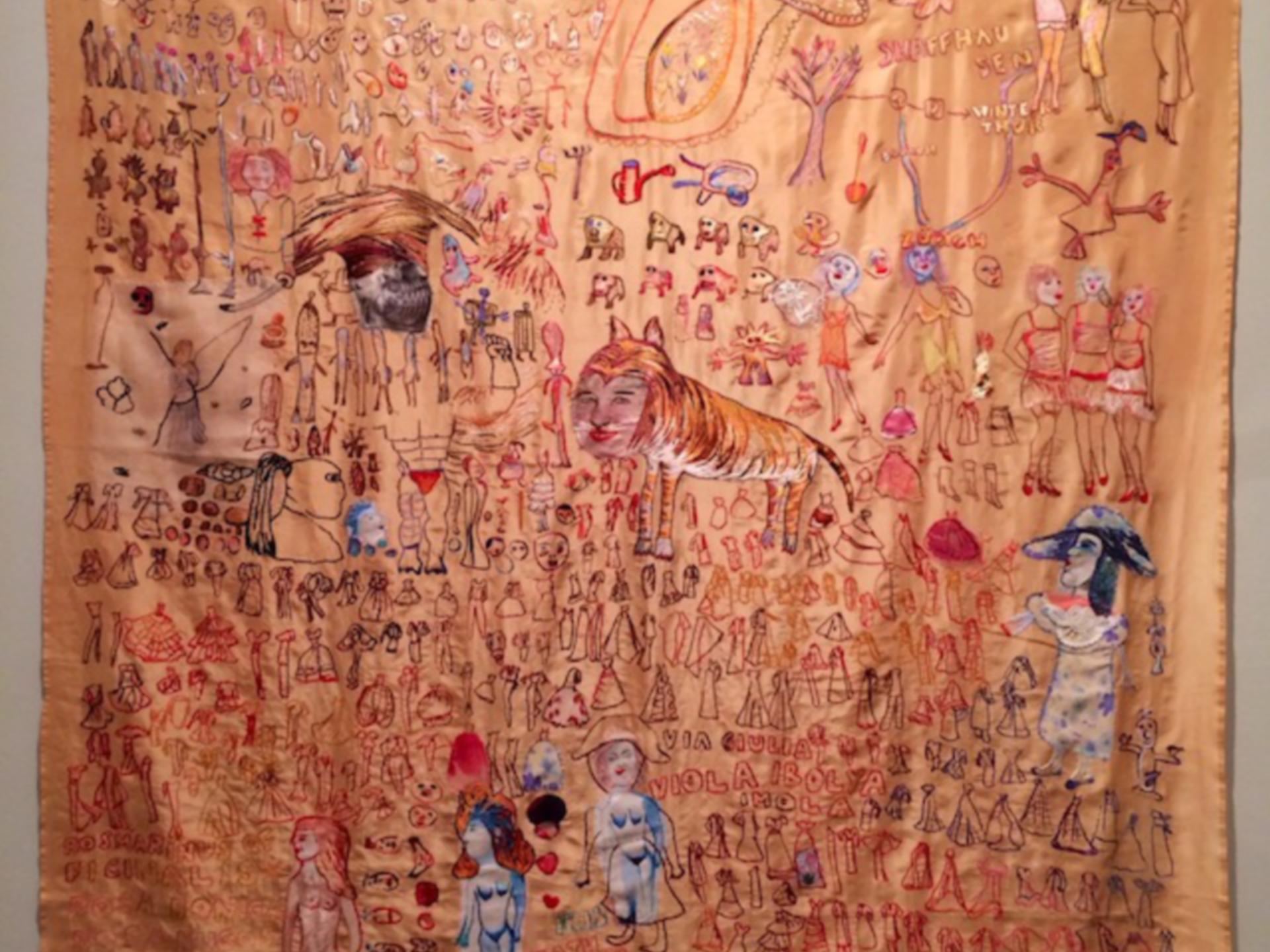

In Vanitas I (2011), Torma constructs an imaginary world from memories of her childhood in Hungary: flower names, paper dolls, fashion plates, comic book villains, layered through soft collage and applique techniques. Koval (2020), examines these visual and material fragments, as gestures of inclusive gathering, where personal history becomes a means for accessing a larger cultural memory, centring the family as both subject and source. Similarly, in my work, I invite elements like braids, satin ribbons, half-forgotten embroidery motifs, weave patterns, and horsehair for an intimate collaboration that reconnects myself with my familial and Hungarian folk heritage, not to replicate, but to recompose a sense of belonging. For me, these familial rituals embedded into the liveliness of the domestic, operate as embodied forms of a remembered belonging, woven through memories of textures, spaces, scents, gestures and surfaces.

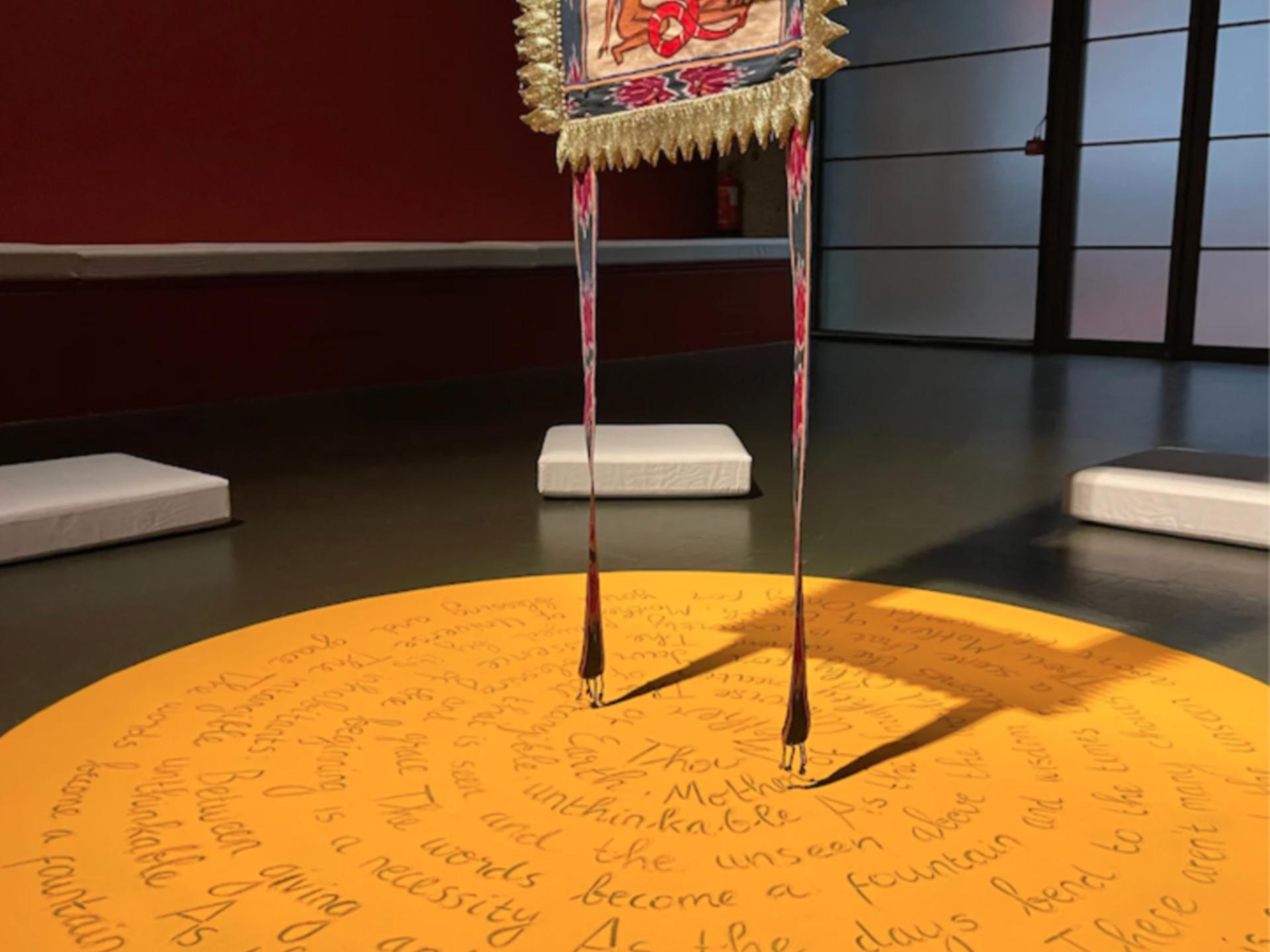

At the centre of Sasmita’s Epilogue (2024), lies a circular floor arrangement of ground turmeric inscribed with a handwritten translation of a Javanese poem. ‘The poem speaks of the year’s most fertile season, a time eagerly anticipated and celebrated through poetry recitations and rituals in Bali (yeoworkshop, 2025). Activating the scent of ground turmeric combined with the curving gesture of the hand that inscribes the unfolding poem, transforms the gallery into a meditative site of ritual, a threshold: transporting the mind into a remembered temporality of the domestic through binding body, material, and memory. In my Embodied memory (2025), enveloping senses of the domestic, extend to the presence of caraway seeds, carried through scent, texture and placement. Deeply embedded into our familial rituals, carraway seeds, not only act as vessels of memory, care and continuity, but for me, as thresholds into a time and space, that offer a deep sense of safety, proximity and belonging.

IV. Home in the Invisible Space. Memory as operative element.

Thaler (2008) examines Anish Kapoor’s Memory (2008), through a metaphysical lens, contemplating the notion when empty is full – an emptiness that is not nothingness, but a condition of possibility, immanent and imminent, that envelops and coexists within all matter. Memory (2008), activates an invisible space, where concealment and revelation coexist, memory is fragmentary, situational, and latent – lingering in a fractured in-between perceptual terrain, where form and formlessness tend toward wholesomeness while remaining comfortably fragmented. Similarly, my In-between realities series (2025), lingers with this idea of the invisible, fragmented space and the intersections of space-memory-perception through fractured, in-between realities. Through memory, as an operative element, situational, and shaped by position, relation and intention, I began to consider the invisible space as fluid and responsive, like a container formed through bodily movement and gesture, where fragmentation becomes a generative mode of unfolding.

At another instance as according to Cvoro (2002), form, in Whiteread’s House (1993) emerges through the act of tracing voids and formlessness by destabilising absence as a category of meaning. In House (1993), memory is understood as residual displacement of the past into the present, a trace that escapes fixed meaning by revealing absence as materially active and effectively charged.

Although my practice operates in a much smaller, transportable, mutable dimension, Untitled (2025), explored unglazed white-stoneware clay as a metaphorical blank slate, to reflect on the residual, and cyclical qualities of memory. I experimented with repetitions of press-moulding, allowing imprints and surfaces to hold traces of time and the touch of the body, where forms emerged between the empty space in the plaster cast and the gestures of my body, as soft containers of emotion that move with me across times and places.

Through In-between realities (2025), and Untitled (2025), I began to contemplate home as latent, fragmented, and situational. An invisible space, that is not empty but full, activated through images retained in our memory.

Although my practice operates in a much smaller, transportable, mutable dimension, Untitled (2025), explored unglazed white-stoneware clay as a metaphorical blank slate, to reflect on the residual, and cyclical qualities of memory. I experimented with repetitions of press-moulding, allowing imprints and surfaces to hold traces of time and the touch of the body, where forms emerged between the empty space in the plaster cast and the gestures of my body, as soft containers of emotion that move with me across times and places.

Through In-between realities (2025), and Untitled (2025), I began to contemplate home as latent, fragmented, and situational. An invisible space, that is not empty but full, activated through images retained in our memory.

V. Home in the interstitial space where memory is threaded into matter

Koval (2020), references Homi K. Bhabha’s definition of the interstitial space as one shaped by the ‘overlap, and displacement of domains of difference’. Fernandez (2020), expands this framework by suggesting, the body exists across multiple spaces simultaneously, whether physical, imagined or remembered, functioning as an extension of space, that in turn, moves through it.

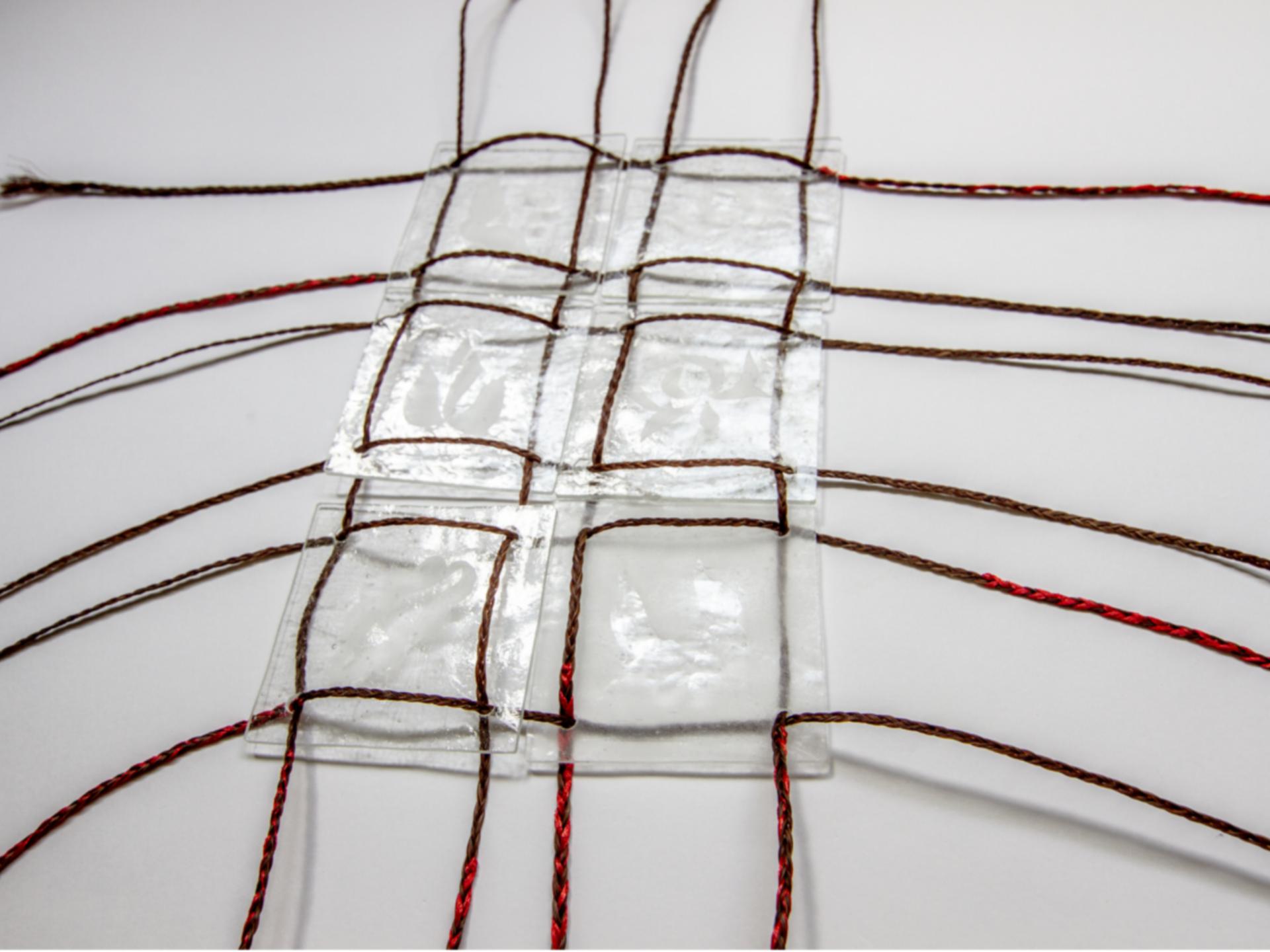

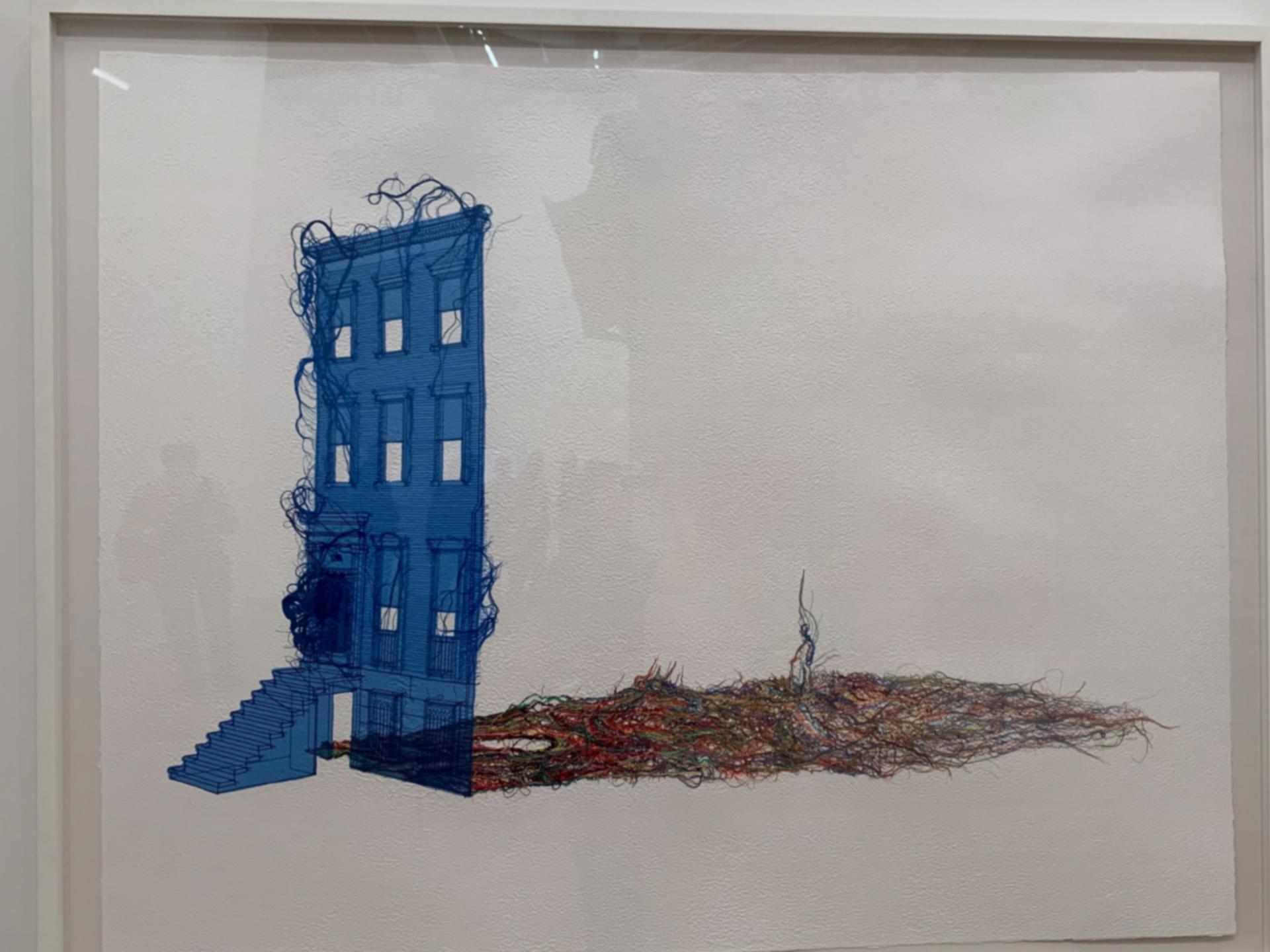

Blueprint (2014) – refencing technical drawings used in construction – explores the idea of home as porous, breathable and mutable, ultimately pondering: when and where is home? The porous façade, more like a membrane than a wall – not a complete building, but a partial skin with doors, windows and roof, from which piles of threads emerge evoking movement and relational energy – depicts a memory of a building the artist once lived. Suggesting that home amalgamates within the interstitial of architectural and emotional spaces, Blueprint (2014) thread spatial memory, motion and the human body into a breathable, temporal fabric.

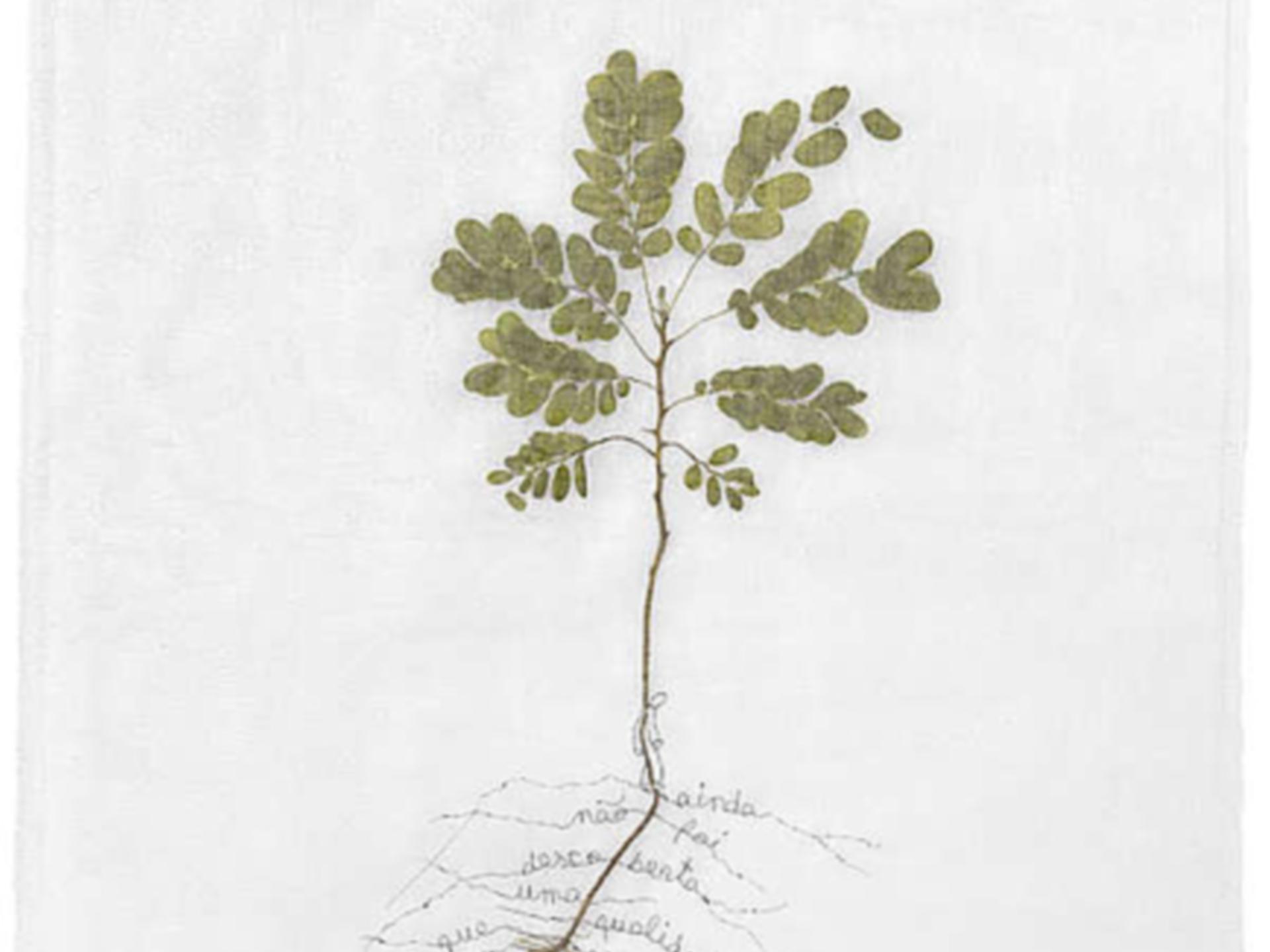

At another instance, Por que Daninhas? (2015), the artist’s own hair, like a structural seam, activates an interstitial space through threading together human and plant DNA, and the gesture of soft-architecture: stitchery.

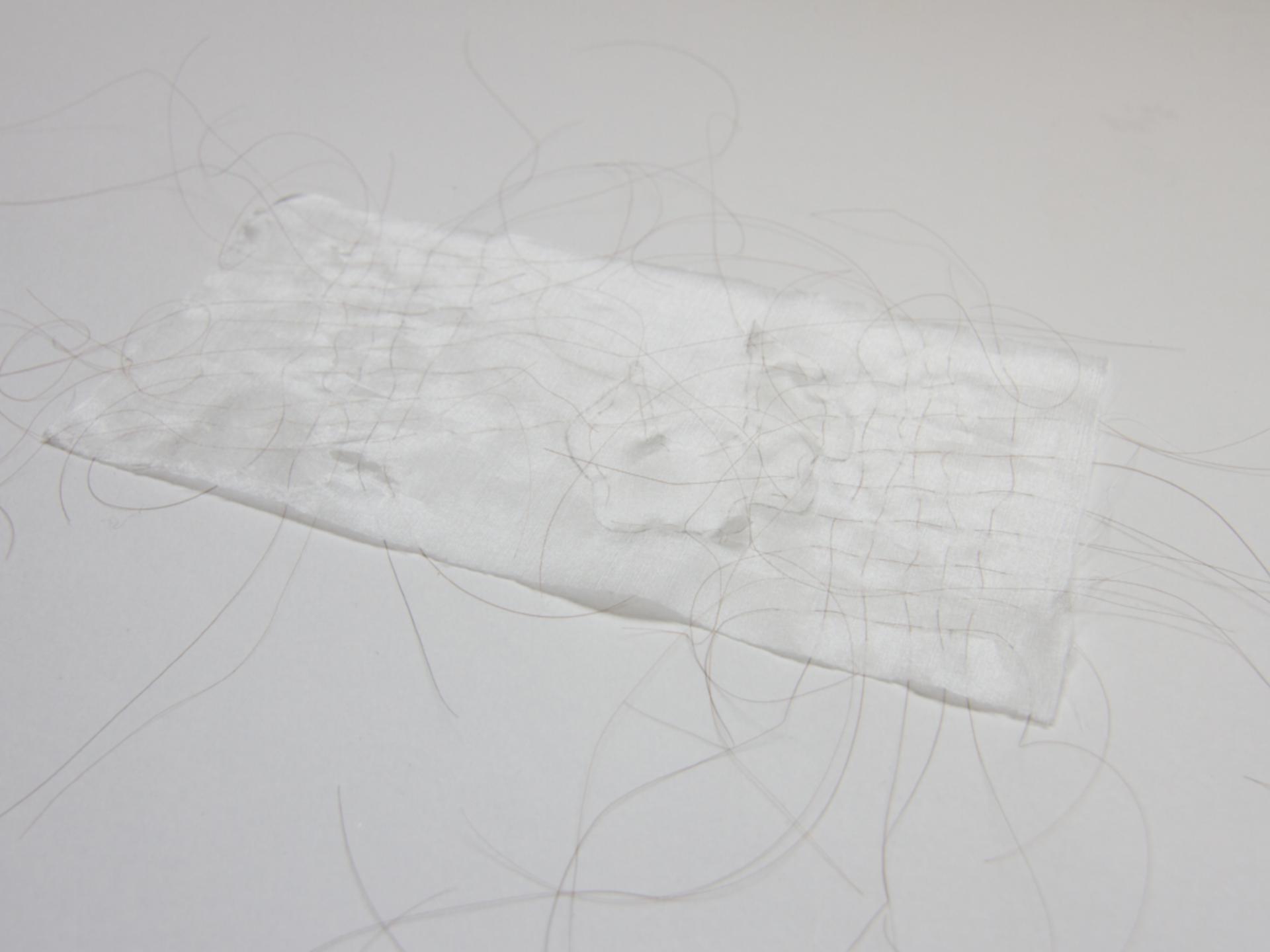

Inspired by Blueprint (2014), and Por que Daninhas? (2015), in Weave of me (2025), I displaced the thread with my own hair, like a memory filament, tracing misremembered shapes of my Mother’s Kalocsa embroideries, that once held and defined home for me, all embedded into an elusive silk-paj, registering residual imprints as a threshold between visibility and invisibility. In a moment that not-yet-met-the-already-gone, where roundness is experienced in the overlaps of fragmentary spatial memories, mediating architecture of the body, and the language of repeated gestures, all threaded into a porous, breathable, temporal fabric, my home is somewhere in the interstitial, hiding in plain sight within the imagined space.

Overall, as I move into Unit 3, I aim to further refine and distil my inquiries around key material and conceptual interests: paper as skin, glass as eye, hair as thread; alongside gestures of braiding, weaving and tracing. Further, I intend to explore how remembered domestic spaces may converge with the void, guiding me toward a more focused artistic practice.

Blueprint (2014) – refencing technical drawings used in construction – explores the idea of home as porous, breathable and mutable, ultimately pondering: when and where is home? The porous façade, more like a membrane than a wall – not a complete building, but a partial skin with doors, windows and roof, from which piles of threads emerge evoking movement and relational energy – depicts a memory of a building the artist once lived. Suggesting that home amalgamates within the interstitial of architectural and emotional spaces, Blueprint (2014) thread spatial memory, motion and the human body into a breathable, temporal fabric.

At another instance, Por que Daninhas? (2015), the artist’s own hair, like a structural seam, activates an interstitial space through threading together human and plant DNA, and the gesture of soft-architecture: stitchery.

Inspired by Blueprint (2014), and Por que Daninhas? (2015), in Weave of me (2025), I displaced the thread with my own hair, like a memory filament, tracing misremembered shapes of my Mother’s Kalocsa embroideries, that once held and defined home for me, all embedded into an elusive silk-paj, registering residual imprints as a threshold between visibility and invisibility. In a moment that not-yet-met-the-already-gone, where roundness is experienced in the overlaps of fragmentary spatial memories, mediating architecture of the body, and the language of repeated gestures, all threaded into a porous, breathable, temporal fabric, my home is somewhere in the interstitial, hiding in plain sight within the imagined space.

Overall, as I move into Unit 3, I aim to further refine and distil my inquiries around key material and conceptual interests: paper as skin, glass as eye, hair as thread; alongside gestures of braiding, weaving and tracing. Further, I intend to explore how remembered domestic spaces may converge with the void, guiding me toward a more focused artistic practice.

Bibliography

Bachelard, G. (2014) ‘The Phenomenology of Roundness’ in The Poetics of Space. 2nd edn. USA: Penguin Books. pp. 247 – 255.

Baldock, J. (2025) 0.1% [Exhibition] London Mithraeum Bloomberg Space. 30 January – 5 July 20205. Available at: https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/mithraeum/item/eab1d93c-c850-4f8d-b7fc-1b3a08ea2c71 (Accessed: 20 February 2025).

Cvoro, U. (2002) ‘The Present Body, the Absent Body, and the Formless’, Art Journal, 61(4), pp. 54–63. doi: 10.1080/00043249.2002.10792136.

Fernandez (2020) ‘Hiding in Plain Sight’ in Artists on Robert Smithson. New York: Dia Art Foundation. pp. 88 – 121.

Frank, P. (2004) ‘Mona Hatoum: hair there and every where’ Art on Paper, 8(1), pp. 40—41.

Hamilton, A. (2010) ciliary. Available at: https://www.annhamiltonstudio.com/objects/ciliary.html (Accessed: 20 April 2025).

Koval, A. (2020) ‘Hybrid Language: The Interstitial Stitches on Anna Torma’s Embroideries’ in J. Amos and L. Binkley (eds) Stitching the self: Identity and the needle arts. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 141 – 154.

Light, J. (2018) Cellscape. Available at: https://www.julielight.co.uk/cellscape (Accessed: 7 May 2025).

Oxford Reference (2025) metaphysics. Available at: https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780198609810.001.0001/acref-9780198609810-e-4516 (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Phaidon (2019), ‘Rosana Palazyan: Por Que Daninas?’ in Vitamin T: Threads & Textiles in Contemporary Art. London: Phaidon Press. pp. 218 – 219.

Rodney, D. (2025) Visceral Cancer [Exhibition]. Whitechapel Gallery, London. 12 February – 4 May 2025. Available at https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/about/press/donald-rodney-visceral-canker/ (Accessed: 30 April 2025).

Sasmita, C. (2024) Into Eternal Land [Exhibition]. The Curve, Barbican, London. 30 January – 21 April 2025. Available at: https://www.barbican.org.uk/exhibition-guides/citra-sasmita-exhibition-guide-1 (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Suh, D.H. (2025) The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House [Exhibition]. Tate Modern, London. 1 May – 19 October 2025. Available at: https://www.citethemrightonline.com/sourcetype?docid=b-9781350927964&tocid=b-9781350927964-160 (Accessed: 3 May 20205).

Thaler, H.L. (2008) ‘When Empty is Full’ in Anish Kapoor: Memory. Berlin: Deutsche Guggenheim, pp. 16 – 20.

Yeo Workshop (2025) Citra Sasmita: Epilogue, 2024. Available at: https://www.yeoworkshop.com/artists/31-citra-sasmita/works/2001-citra-sasmita-epilogue-2024/ (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Bachelard, G. (2014) ‘The Phenomenology of Roundness’ in The Poetics of Space. 2nd edn. USA: Penguin Books. pp. 247 – 255.

Baldock, J. (2025) 0.1% [Exhibition] London Mithraeum Bloomberg Space. 30 January – 5 July 20205. Available at: https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/mithraeum/item/eab1d93c-c850-4f8d-b7fc-1b3a08ea2c71 (Accessed: 20 February 2025).

Cvoro, U. (2002) ‘The Present Body, the Absent Body, and the Formless’, Art Journal, 61(4), pp. 54–63. doi: 10.1080/00043249.2002.10792136.

Fernandez (2020) ‘Hiding in Plain Sight’ in Artists on Robert Smithson. New York: Dia Art Foundation. pp. 88 – 121.

Frank, P. (2004) ‘Mona Hatoum: hair there and every where’ Art on Paper, 8(1), pp. 40—41.

Hamilton, A. (2010) ciliary. Available at: https://www.annhamiltonstudio.com/objects/ciliary.html (Accessed: 20 April 2025).

Koval, A. (2020) ‘Hybrid Language: The Interstitial Stitches on Anna Torma’s Embroideries’ in J. Amos and L. Binkley (eds) Stitching the self: Identity and the needle arts. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 141 – 154.

Light, J. (2018) Cellscape. Available at: https://www.julielight.co.uk/cellscape (Accessed: 7 May 2025).

Oxford Reference (2025) metaphysics. Available at: https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780198609810.001.0001/acref-9780198609810-e-4516 (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Phaidon (2019), ‘Rosana Palazyan: Por Que Daninas?’ in Vitamin T: Threads & Textiles in Contemporary Art. London: Phaidon Press. pp. 218 – 219.

Rodney, D. (2025) Visceral Cancer [Exhibition]. Whitechapel Gallery, London. 12 February – 4 May 2025. Available at https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/about/press/donald-rodney-visceral-canker/ (Accessed: 30 April 2025).

Sasmita, C. (2024) Into Eternal Land [Exhibition]. The Curve, Barbican, London. 30 January – 21 April 2025. Available at: https://www.barbican.org.uk/exhibition-guides/citra-sasmita-exhibition-guide-1 (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Suh, D.H. (2025) The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House [Exhibition]. Tate Modern, London. 1 May – 19 October 2025. Available at: https://www.citethemrightonline.com/sourcetype?docid=b-9781350927964&tocid=b-9781350927964-160 (Accessed: 3 May 20205).

Thaler, H.L. (2008) ‘When Empty is Full’ in Anish Kapoor: Memory. Berlin: Deutsche Guggenheim, pp. 16 – 20.

Yeo Workshop (2025) Citra Sasmita: Epilogue, 2024. Available at: https://www.yeoworkshop.com/artists/31-citra-sasmita/works/2001-citra-sasmita-epilogue-2024/ (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

1 Elementary phenomenology, as distinct from phenomenology grounded in logical sequences, grants us the benefits of elementariness, a return to foundational, sensory and poetic experiences of being, a phenomenology that Bachelard (2014) regards as the phenomenology of the imagination.

2 Metaphysics= the branch of philosophy that deals with the first principles of things, including abstract concepts such as being, knowing, identity, time, and space.